Hairetical: A History of Hair in my Sikh Family

Graphics by Daija (@freshed__squeezed)

Having been raised in a devout Sikh household, I am, unquestionably, an expert in avoiding hairy situations.

In my religion, hair is a sacred object, and it is seen as a sin, practically hair-etical, to cut one’s hair. Accordingly, all the adults on my mother’s side of the family have unshorn hair. This is slightly different for everyone: the men tie their hair up in turbans every day, while the women wear their hair in buns or braids. My mother and grandmother used to both wear their hair down every day, naturally pin-straight and thigh-grazing, the kind of hair that their staff at the hospital would gawk at as they walked down the hallways. Even as a little girl, I was raised to aspire to that kind of hair. Every time I walked into the hospital, the staff would come up to me and ask, “How long is your hair now? Is it as long as Dr Ramnik’s yet?”

It wasn’t as long as my mother’s was yet, but it was already very long in its own right, going past my skirts’ hemlines and flowing in waves around me every time there was a breeze. My classmates petted it and fawned over it. And initially, so did I.

But my Rapunzel-like hair had a mind of its own. It wasn’t pin-straight like that of the other women in my family; it fell loosely, openly, nakedly. I hated leaving it untied because it would keep getting tangled in everything, from doorknobs to other people’s bracelets. I used to swim every day back then, and my hair would never fit into the swim caps because none of them were big enough. So I would have to wash my hair every day, because it would always get wet in the pool, adding nearly an hour to my daily routine to wash and dry three feet of hair. It got in my way, tripped me up, tickled my eyes, ears, lips. It wasn’t my shield, the way it was for my mother and grandmother. It didn’t cover me. If anything, it exposed me.

My life was mal aux Cheveux: literally, ‘hair sickness’ (which also means ‘hangover’ in French). This was apt: my hair hung over my routine, my clothing, my range of activities: It hung like a pall over my sense of identity as a woman, writer, activist. Who, exactly, was in charge here? I complained to my mother, who, in return, brought me back a book from the Gurudwara, the Sikhs’ place of worship. It was very beautifully illustrated and spoke eloquently of the beauty of Sikhism. I still remember it having this one passage about ‘Kesh’ (the word in Sikhism for holy, unshorn hair):

"Ah! Well, let my hair grow long;... I cannot forget the knot He tied on my head; It is sacred, it is his mark of remembrance. The Master has bathed me in the light of suns not yet seen; There is eternity bound in this tender fragile knot. I touch the sky when I touch my hair, and a thousand stars twinkle through the night.”

But still, my hair became a burden--a weight, both literal and figurative, on my shoulders. There it was, getting onto the bus with me in the morning, my braid getting caught in my bus mates’ bags’ zippers; it was there at ballet class, all .5 pounds of it, not able to hold all its weight in a bun as I twirled and pirouetted. I’d open a notebook, and there it would be again: a forty inch-long strand, shedding because haircare is practically impossible when you have that much of it and aren’t allowed to do anything about your split ends. I often imagined what it would be like to be free of it, but guiltily tucked my fantasies aside.

As I got older, I started seeing the gaps in my family’s reasoning for following the practice of kesh. Why, for example, do the men wear turbans, while women’s hair has to be worn free? Diving into Sikh literature, I found that all Sikhs were instructed by our Guru to wear turbans: the turban was chosen because at the time it was a symbol of aristocracy, and allowing women and lower-caste people to wear it aimed to abolish the structure within itself. But most Sikh women today don’t wear turbans: they are seen as a masculine accessory. I began feeling that the male gaze dictated a Sikh women’s practices almost as much as the Guru’s teaching; I started losing faith in this superficial tradition, though I wasn’t ready, just yet, to take the plunge and be seen as ‘different’ or ‘disobedient.’

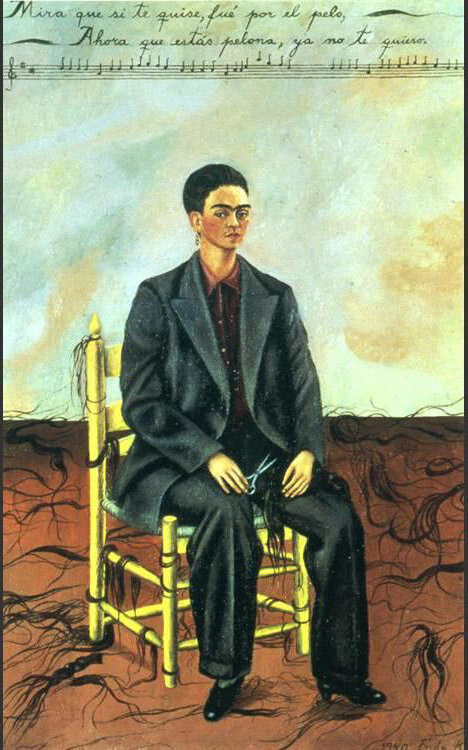

So when I first saw “Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair” by Frida Kahlo, I saw myself in it. In the painting, Kahlo depicts herself sitting on a chair in a bare room, staring directly at the viewer, wearing a man’s suit and with a man’s haircut, holding a pair of scissors, with locks of her hair strewn all around her. Inscribed at the very top are lyrics from a Mexican folk song, about a relationship ending because the singer’s lover cut her hair: “Mira que si te quise, fué por el pelo, Ahora que estás pelona, ya no te quiero”—which roughly translates to “I only loved you for your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore.”

Frida Kahlo “Self Portrait with Cropped Hair.” - 1940

Frida’s stony gaze spoke to me. I connected her act of cutting her hair to my own inability to make that same decision for myself. I felt trapped by my religion to live my whole life with three feet of hair trailing after me, against my will, like a sinister shadow. Just like Frida felt like she had to do certain things to please her now ex-husband, Diego Rivera, I felt I had to keep my hair long because I was born into a certain way of living. The steely expression on Frida’s face as she stood in the middle, with locks of her freshly-cut hair surrounding her, conveyed a sense of freedom: a chance to finally make choices for herself, which was a direct result of her no longer being bound to her relationship with Rivera. I was surprised by how much I envied her.

“I only loved you for your hair. “Seeing Frida got me thinking about what my religion actually means to me, and to what extent I want to follow beliefs that have been propagated over generations. The lyrics of the Spanish song reflect a seemingly simple dilemma, but it’s what I had been afraid all these years that God would do to me. I’d spent my whole life thinking God would love me less, would think of me as unfaithful if I cut my hair. But would He really, actually do that, as long as I still devoted myself to him, still prayed to Him, still visited the Gurudwara on a weekly basis? Does simply cutting my hair mean I am less faithful to Him?

So I decided to test my faith -- I got a haircut. With my sister, I visited the salon at which I was regularly taken by my mother to wax my eyebrows, my mustache (hair which, of course, I was not theologically bound to retain). After spending my life with hair that draped to my mid-thigh, when the hairdresser asked what kind of haircut I wanted, I took a deep breath, thought about it for a few seconds, and said: “Make it so short that it doesn’t even dare to touch my chin. Free me of it.” The hairdresser clapped his hands.

Two hours later, I had a new look and a new outlook. Three feet of hair, fifteen years, a few ounces. I felt lighter. I didn’t care what my mother would say. Because I suddenly knew the truth.

I chose to end my hair, punctuate it and round it off. But what I was most surprised about was the way this actually felt like a beginning: a reclamation of my own self. Hair grows: that is its teleology. But so do people, through the exercise of their will and judgement, through the operation of their criticality and scepticism, through their ability to question received wisdom and, occasionally, challenge the status quo. Today, my hair is but a memory, existing in pictures, in my mother’s occasional comment (but it was so long and beautiful…). But I am closer than ever to God, our relationship newly empowered with my will to see it through in my own way. I am still a Sikh, even though I have short hair; except, now, more than ever, I ‘seek’ my own answers.

By Diya Sabharwal

(she/her)

Edited by: Halima Jibril