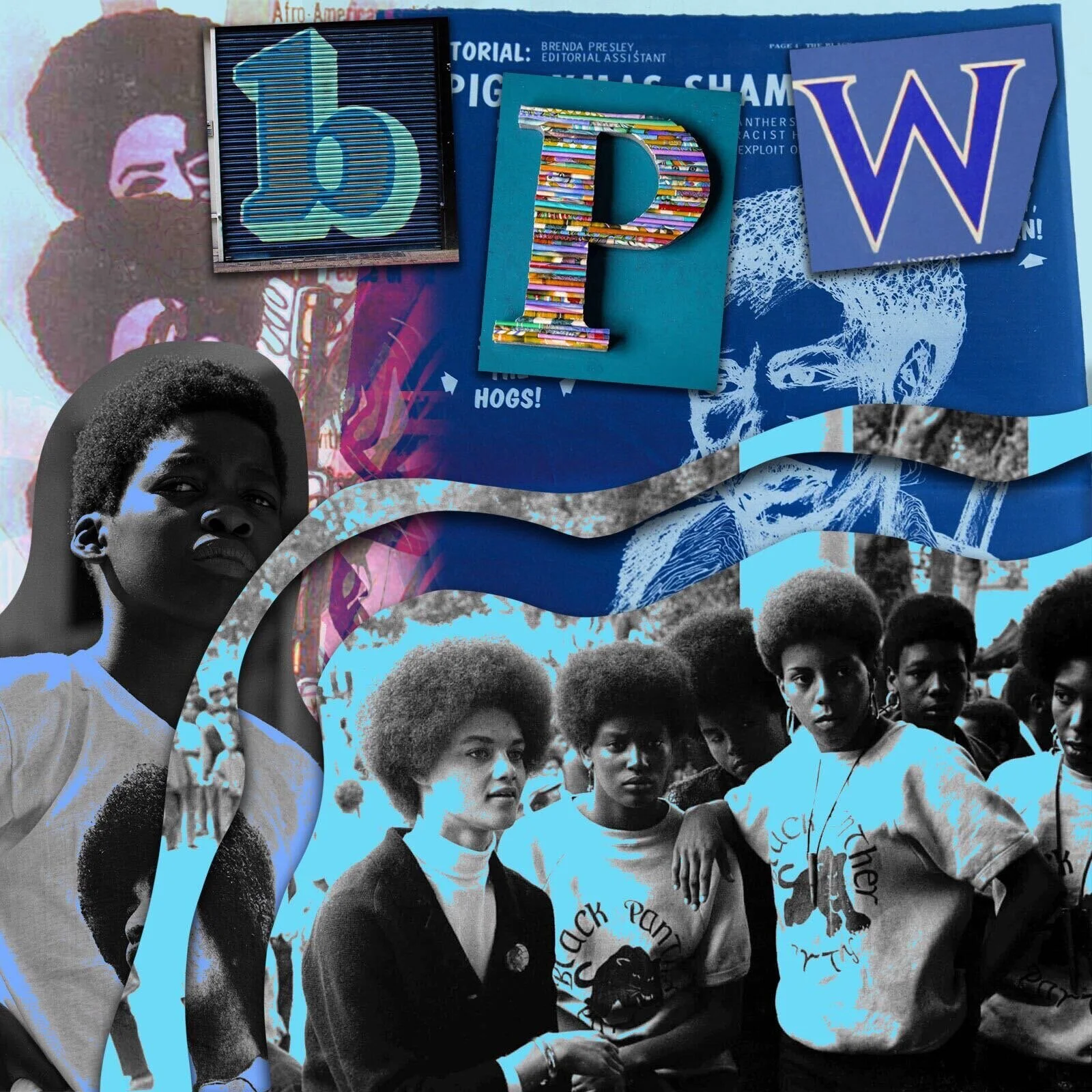

The Her-Story of the Black Panther Party: How Panther Women Shaped the Revolution

Graphic by Maya Swift

TW: Rape and sexual assault mentions

CHAUVINIST (NOUN): A person displaying aggressive or exaggerated patriotism

When I was taught about the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence (BPP) in school, it was tagged along at the end of the Civil Rights Movement and labelled as a dangerous organisation; the ones who ruined civil rights for black Americans. Indeed, the Black Panthers were and still are criticised for their militant strategies, their male dominance and as a result their male chauvinism that led to the party’s failures. Yet, in my second year of university, I was required to do a presentation on the Black Panther Party, where I uncovered evidence that subverted these views, showing that actually, the Panthers were highly successful in many ways and that the women of the party were largely responsible for this success. Not only did they make up a significant portion of party membership and made important contributions, but they also worked extremely hard to make the party intersectional.

Resisting Male Chauvinism

Just three years after the party was founded, two-thirds of its members were women. The presence of these women was vital for stomping out the traces of male chauvinism prevalent in the BPP. They immediately protested the label of ‘Pantherettes’ used to describe Panther women and assign them alternative roles to men. They highlighted that the delegation of roles in relation to sex as well as male chauvinist tendencies was exactly the kind of bourgeoisie behaviour that they were supposed to be fighting against. To subjugate these gendered roles, they swapped responsibilities to challenge typical gender stereotypes: women patrolled the streets with guns while men worked in the kitchens at their free breakfast programs (which was arguably the most successful concept implemented by the BPP that still remains an important US welfare program today). Chauvinism did prevail among some party members e.g. Eldridge Cleaver, who was a convicted rapist and wrote Soul on Ice: a memoir justifying the practice of rape on black women to rape white women successfully. Still, the presence and contributions of women in the revolutionary movement, given the politics of respectability that governed black women in the 1960s/1970s, was revolutionary in itself.

Panther women’s contributions to Panther discourse, most notably The Black Panther newspaper, allowed women to have some control over how they were portrayed. The Black Panther was the main form of direct communication between the Panthers and the public, and the political cartoons and images were the first thing that readers would look at. The work of Tarika Lewis, pen name Matilaba, was therefore important for representing the image of Panther women, whom she portrayed as strong and militant. The articles in the newspaper also became a safe space to speak about reproductive rights, including forced hysterectomies. Speaking about forced hysterectomies was incredibly important since the contemporary media was certainly not concerned about sharing news on the underground genocide of black people, and so the newspaper became a space to reveal these truths. After all, with the circulation of approximately 125,000 newspapers from 1969-1970, word would certainly get out.

The successes of women in the party can be singularly exemplified by Elaine Brown’s appointment as party chairwoman in 1974. Her leadership led to the delegation of many women into the central committee of Panthers, who conducted projects that had long-lasting effects, such as the establishment of Oakland Community School which is now a model for liberatory education. Although male chauvinism was an issue prevalent in the BPP, Panther women worked hard to stamp it out and as a result, created a much more open and progressive party.

Sisterhood Beyond the Colour Line

While we might consider many of the ideologies behind Panther women’s actions to be feminist, it is important to note that most did not identify with the second-wave feminist movement that was active at the time. When Panther Safiya Bukhari defiantly stated, “I am not a feminist, I am a revolutionary”, she reflected the beliefs of the majority of Panther women. For the term “feminist” was associated with white western women’s concerns and desires for opportunities in the workforce. But black women had been working since their enslavement – they felt that there were much larger and different concerns for black women in the United States. So, there was little collaboration between Panther women and the women’s movements for liberation.

Despite this, there was still a need to address the issues that were unique to black women. This was also recognised by many Panther women, including Assata Shakur who said, “it is imperative to our struggle that we build a strong black women’s movement.” There was a black second-wave feminist movement active at the time advocating for black women’s struggles, but there is little evidence of interactions between these movements and the BPP. Still, they certainly shared ideologies and this can be seen by examining the Combahee River Collective’s (CRC) intersectionality. The CRC, formed in 1974, was an incredibly important black feminist lesbian organisation that were early to recognise the intersection of racism and sexism. Intersectionality was also considered necessary for liberation by prominent members and affiliates of the BPP including Assata Shakur, Kathleen Cleaver and Toni Morrison.

Universal Liberation

Panther women applied this intersectional thought to additionally incorporate the struggles of different groups and to work with different organisations to better themselves. This included the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who had deep connections with the BPP from the outset. The women leaders of SNCC, for instance, Gloria Richardson and Diane Nash, had inspired Panther Kathleen Cleaver to begin revolutionary action. The infrastructure of SNCC too was a big inspiration for the BPP – they had autonomous structures with a focus on creating indigenous leadership. This structure was created by a founding SNCC member, Ella Baker, and passed on to the BPP by women such as Kathleen Cleaver which highlights the importance of women members in tying the two movements together.

Although Panther women could not form strong ties with the second-wave feminist movement, they were strong supporters of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). There was a definite expression of homophobia amongst Panther men, who sometimes outwardly expressed their refusal to support the movement and used derogatory language against members of the LGBTQ+ community. But Panther women, such as Tupac’s mother Afeni Shakur, offered an olive branch to LGBTQ+ communities. An article published in Come Out! newspaper (a GLF publication) detailed that Shakur had come to assist the GLF in 1970 when two of their members had been arrested. It also went on to claim that Shakur had spoken to GLF members of her revolutionary a struggle and argued for the development of the BPP into, “an intersectional organisation concerned with the struggle of all oppressed people around the world.” Although there were several attempts and failures at forming bonds between the BPP and GLF, Panther women like Shakur could make connections with the LGBTQ+ communities and individually assist them in their causes.

A final group that Panther women forged a strong relationship with and were strongly inspired by were the Vietnamese women soldiers fighting for the revolution. Many struggles for liberation at this time saw the “East” as a revolutionary model for how western radicals could fight against racism, sexism and classism. And so, both Panther men and women were active in trying to gain momentum for the Vietnamese liberation struggle. Panther women were especially inspired by revolutionary Vietnamese women holding leadership roles in the National Liberation Front and those who were juggling the roles of being a mother, and a revolutionary. What Panther women may not have understood here, however, was that many of these leaders and mothers were under immense pressure by men in their lives and additionally were hypersexualised and controlled by revolutionary men. Still, the appreciation of these Vietnamese women by Panther women was more celebratory than the Hanoi government had ever been and they greatly inspired Panther women to find strength in themselves.

Today, Panther women have been an inspirational source for many black American women fighting for their liberty. A new research project, the Intersectional Black Panther Party History Project, conducted by a group of black American female historians aims to eventually build a reader on BPP women’s experiences through the lens of gender and sexuality; something that has previously been missing in the historical record. The need to document Panther women’s work and struggles is becoming increasingly necessary in an America where, as of 2017, sexual violence is the most reported crime and black women are among the majority of victims. In an effort to bring visibility to this violence, Black Women’s Blueprint is an organisation concerned with placing black women’s struggles in the wider context of racial disparity, whilst using an intersectional feminist approach to do so. In tackling sexual abuse and campaigning for reproductive rights for all, the organisation is redefining what it means to be a black woman in America, just as Panther women have done before them. 54 years after the establishment of the BPP, black American women are still struggling, but are still finding inspiration from the Panther women that came before them.

Recommended Reading

Ashley Farmer, Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era

Its About Time (The official website for the Black Panther Party alumni)

The Freedom Archives (An expansive archive containing videos, audio recordings, articles and more produced by revolutionary movements for liberation from the late 1960s to the mid-1990s)

Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story

Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism and Feminism During the Vietnam Era

This is a shortened version of Leah’s dissertation written under the same title for her MA (Hons) in History at the University of Glasgow in 2020.

By Leah Monteiro,

(she/her)

IG & Twitter: @leahzinha_

Graphic by Maya Swift (IG: @mayaisabelaswift)

Edited by Halima Jibril (IG:@h.alimaa)